China has become a heavyweight in robotics and AI. With the world’s largest market for industrial robots, a surge of domestic manufacturers, and breakthroughs in humanoid robots and embodied intelligence, the country is increasingly shaping global technology trends. A unique industrial ecosystem, a vast talent pool, and targeted government initiatives give the local industry decisive momentum. European companies need to take this dynamic seriously if they want to remain competitive.

Why the world must take Chinese robotics and AI seriously

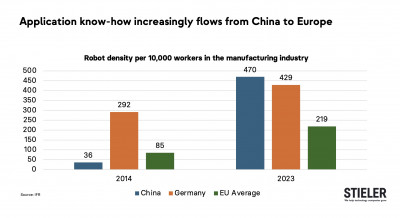

Since 2014, China has been the largest robot market in the world. In recent years its share of global installations has held steadily at around 50 %. Twelve years ago, Germany’s robot density was more than ten times higher than China’s—now China has overtaken Germany. Compared with the EU average, China’s robot density is now more than twice as high. Application know‑how increasingly flows in the opposite direction—from China to Europe.

At the same time, the domestic market share of Chinese industrial‑robot manufacturers has risen from below 30 % to over 50 %. In collaborative robots, where the initial development gap was smaller, the market share is already 90 %, and in mobile robots even 95 %.

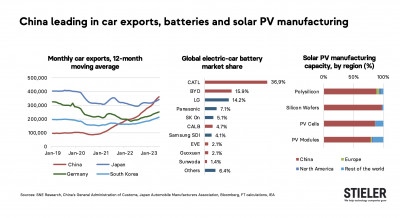

China leads in EVs, batteries, photovoltaics and drones

For years, there was a saying that Europe had to stay at least one technological step ahead to offset localization and know‑how transfer. That is no longer true for many future industries. China is now at the forefront of electric vehicles, batteries, photovoltaics and drones. In the rollout of autonomous driving, China is neck‑and‑neck with the United States. According to a recent study by JP Morgan, more than half of the listed companies in the humanoid‑robot supply chain are Chinese. The industrial ecosystem that has emerged over the past decades is unique. In mechatronics, no one can bring new products to market maturity as quickly and then manufacture them in high quality at competitive prices. As of spring 2025, a considerable portion of the hardware for Tesla’s Optimus is expected to come from China. German start‑ups in the field already source robot arms and components such as joints with integrated force sensors from China. Despite political talk about derisking, a good share of our German clients are therefore expanding their R&D capacity in China – to stay competitive.

Leading through a larger talent pool

China’s emphasis on STEM education is paying off. The country produces roughly 3.5 times as many science graduates as the 27 EU member states and about 4.5 times as many as the United States. Although the gap between top universities and institutions in the hinterland can be enormous, the numbers illustrate the sheer manpower that can be thrown at technical problems.

Chinese companies are setting the tone in AI

Chinese companies are breaking new ground in AI. Providers from China have long been leaders in machine vision. In late January Deepseek caused a stir by unveiling a powerful, resource‑efficient open‑source large language model that runs locally on hardware costing about €6,000—distilled versions even run on a MacBook or iPhone. Anyone can further develop the model for their own purposes. The consequence: applications emerge that would otherwise have lacked commercial justification, accelerating the global adoption of AI. We see a similar trend in robotics—much cheaper mobile manipulators or robot cells will open up new applications in Europe as well.

The shortage of high‑performance domestic semiconductors is still a weak point. On the one hand China’s progress toward technological self‑sufficiency has been faster than expected; the US sanctions imposed over the past six years have opened unique opportunities for new players along the supply chain. On the other hand, the demand for compute will rise massively. While there have so far been sufficient resources to train LLMs and simple VLMs, models that have to represent the physical world are far more complex.

Deepseek and Unitree exemplify new momentum

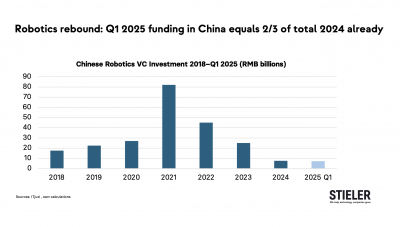

After several financially lean years for the Chinese tech sector—with a drastic drop in venture capital and a record low in IPOs—Beijing is trying to reinvigorate the field. In February, Xi Jinping met with leading tech entrepreneurs. Jack Ma was publicly rehabilitated. Companies such as Deepseek and Unitree stand for a new dynamism.

In March the Chinese government announced a new US $138 billion VC guidance fund that will support robotics as well as AI, quantum computing and hydrogen storage on a market‑oriented basis. If the fund really follows market mechanisms, it is the right approach. Deep tech needs time.

Where do Chinese robot makers still face hurdles?

All this shows that Chinese manufacturers of industrial robots (including Estun, Innovance, Efort and Rokae) or cobots (Aubo, Jaka, Dobot and Elite Robots) must be taken very seriously—as must the new players entering the market with humanoid robots and embodied AI. The prospects are good that China will decisively shape the future of intelligent robotics.

Nevertheless, Chinese suppliers still face challenges when entering the German and wider European market:

Large‑payload industrial robots—They are not yet winning contracts with automotive OEMs in Europe, but they are at the table and pushing prices down.

Among German end users we still observe considerable skepticism about the reliability of local service. Established Western and Japanese vendors continue to have the better networks.

Another field where Chinese suppliers still have to learn is compliance with local standards: applications usually cannot be transferred one‑to‑one.

AI in particular is heavily regulated in Germany and Europe. Many questions remain unanswered for humanoid robots, and there are serious concerns about data security as connectivity increases.

How should Europe react?

How should Germany and Europe respond to China’s strengths in robotics? We see four points that are under‑represented in the public debate:

1. A first‑class robotics industry needs a strong home market

Germany has a strong robotics and automation sector partly because it long built the best cars in the world. However, we currently have a 30 % location cost disadvantage compared with China. Established German companies are investing more and more elsewhere. Start‑ups that sell into end industries working short‑time work face an unfriendly environment. Better networking of industry, science and politics is welcome, but what we need above all is stronger domestic demand. The remedy: massive deregulation and more attractive framework conditions.

2. More powerful investor ecosystem

It has become easier in Germany to raise a few million in seed capital. What is missing is tighter integration between early‑stage investors such as business angels or state programs and later‑stage investors. France’s Tibi initiative shows how larger VC funds can emerge. Hubs such as those around TU Munich, ETH Zurich or Odense with support networks and good access to capital still have potential for improvement. Some argue we need something like DARPA, which generates solid sales for strategically important start‑ups over years.

3. A culture of courage and entrepreneurship

In large parts of Central Europe, it is frowned upon to become wealthy through entrepreneurial success—more so than in the USA and even than in communist‑ruled China. Founding a company offers fulfilling work, but also comes with risk and sacrifice. Red tape and lack of social recognition discourage founders. Over‑regulation has misdirected the focus of established companies as well. We need more appetite for risk and speed again.

4. More strategic autonomy

The USA currently accounts for about 60 % of global AI training capacity, China for around 30 %—Europe for only 4–5 %. And the Old Continent risks falling further behind. We lack our own GPU technologies and energy prices are too high. Embodied intelligence will require far more compute in the future. Promising approaches such as Trumpf’s photonic processors could give German industry a lead again. The help these new technologies gain traction requires industry consortia and smart government support.

Want to know more?

Order our free White Paper to learn more about the leading robotics manufacturers, humanoids, and embodied intelligence in China.